The state budget is usually the most important piece of legislation passed in every legislative session, but it has a timetable and terminology that can be confusing. To help demystify the process, we offer the following overview and a glossary of state budget terms.

Few issues so dominate the legislative process as the state budget. The tax and spending plan captures the attention of the governor, lawmakers, state agencies, lobbyists, and the media for months every odd-numbered year.

With control of state government now split between Democratic Governor Tony Evers and majority Republicans in the Legislature, the process will likely take on even more political drama and, potentially, delays in adoption of a final product.

For those unfamiliar with state government, the budget can seem intimidating, with a language and a timeline all its own. Yet, once the jargon is stripped away, the process and the concepts are all fairly simple. To help readers understand this process—and what is at stake—we offer an overview of several major decision points, budget elements, and issues facing state leaders.

Two-year Plan

The state budget encompasses two fiscal years, or a biennium, such as from 2017-19 (the current budget) or 2019-21 (the next one). A fiscal year runs from July 1 of one year to June 30 of the next. Ideally, the 2019-21 budget should be in place by July 1of this year; if not, spending will continue at current levels until the new budget is enacted.

The budget process begins in the fall of each even-numbered year when agencies submit their requests to the governor. These spending proposals are balanced against projected revenues as the governor begins drafting the budget bill. If the governor’s office changes hands after an election in the fall, delays may creep into the preparation process, as have occurred this year.

The public portion of the budget process begins in February or March when the governor officially presents the budget to the Legislature. The budget bill is lengthy, typically running more than 1,000 pages. It includes expenditures for every agency and program in state government, and revenues from taxes, fees, and federal aids. The 2017-19 budget includes more than $75.7 billion in total expenditures.

Budgets Within the Budget

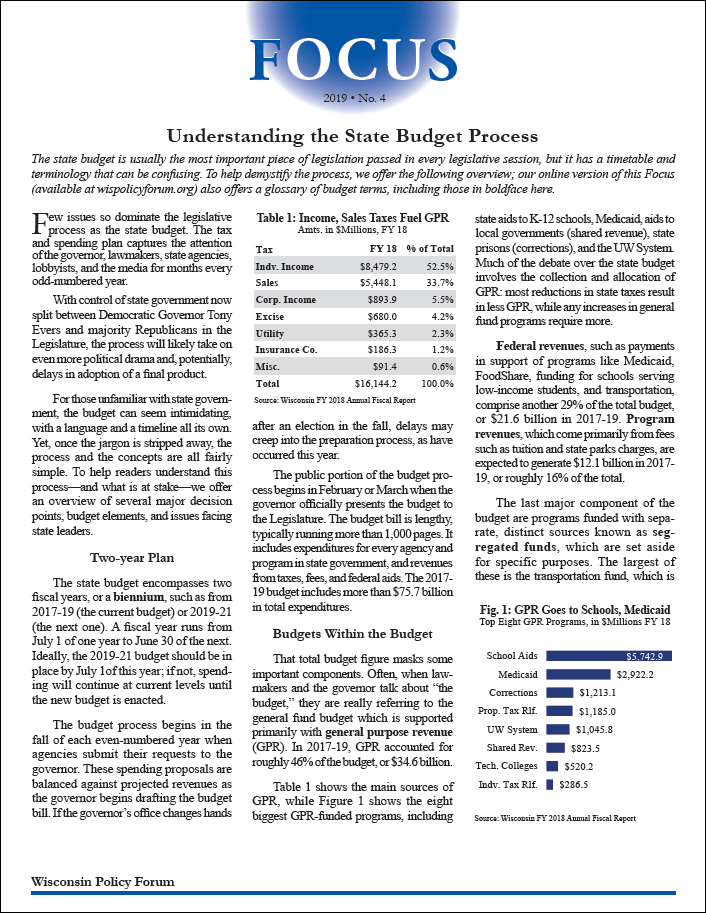

That total budget figure masks some important components. Often, when lawmakers and the governor talk about “the budget,” they are really referring to the general fund budget which is supported primarily with general purpose revenue (GPR). In 2017-19, GPR accounted for roughly 46% of the budget, or $34.6 billion.

| Tax | FY 18 | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Indv. Income | $8,479.2 | 52.5% |

| Sales | $5,448.1 | 33.7% |

| Corp. Income | $893.9 | 5.5% |

| Excise | $680.0 | 4.2% |

| Utility | $365.3 | 2.3% |

| Insurance Co. | $186.3 | 1.2% |

| Misc. | $91.4 | 0.6% |

| Total | $16,144.2 | 100.0% |

Table 1 shows the main sources of GPR, while Figure 1 shows the eight biggest GPR-funded programs, including state aids to K-12 schools, Medicaid, aids to local governments (shared revenue), state prisons (corrections), and the UW System. Much of the debate over the state budget involves the collection and allocation of GPR: most reductions in state taxes result in less GPR, while any increases in general fund programs require more.

Federal revenues, such as payments in support of programs like Medicaid, FoodShare, funding for schools serving low-income students, and transportation, comprise another 29% of the total budget, or $21.6 billion in 2017-19. Program revenues, which come primarily from fees such as tuition and state parks charges, are expected to generate $12.1 billion in 2017-19, or roughly 16% of the total.

The last major component of the budget are programs funded with separate, distinct sources known as segregated funds, which are set aside for specific purposes. The largest of these is the transportation fund, which is comprised mainly of revenues from the state’s 32.9-cent-per-gallon gas tax and $75 vehicle registration fees. In part because of slowing growth in these revenue sources, transportation funding is likely to be one of the most contentious issues in the upcoming budget deliberations. Segregated funds are expected to comprise about 10% of the 2017-19 budget, or $7.4 billion.

Legislature’s Role

Once the budget bill is introduced, it goes to a single legislative committee, the Joint Committee on Finance (JCF), for action. The JCF, which includes members from both legislative houses, is considered one of the most powerful budget committees in the country because it acts on the budget, as well as specific taxes and spending items. Those are usually split among several committees in other states and Congress. Typically, the JCF holds public hearings on the bill in early spring, then begins amending it in May.

When JCF’s work is done, the bill moves to each legislative house for further amendments and approval. If the Assembly and Senate do not agree on a final version, a conference committee made up of leaders from both houses works out a compromise. In years when control of the Legislature has been split, conference committees have taken months to reach a final deal. This year both houses are controlled by Republicans, who may be able to reach an agreement among themselves more quickly. However, timely passage in the Legislature may not guarantee a deal with the governor, whose vetoes could also delay enactment.

Governor’s Pen

The final bill then heads to the governor, who may sign it; let it take effect without signing it; veto it entirely; or use his powerful partial veto to reduce spending or strike out words or phrases in the bill. Although lawmakers may override the governor’s vetoes by a two-thirds vote, they have not done so since 1985.